01 Jan Essays on the Holocaust

“Pure Junk”,

A Personal Commentary:

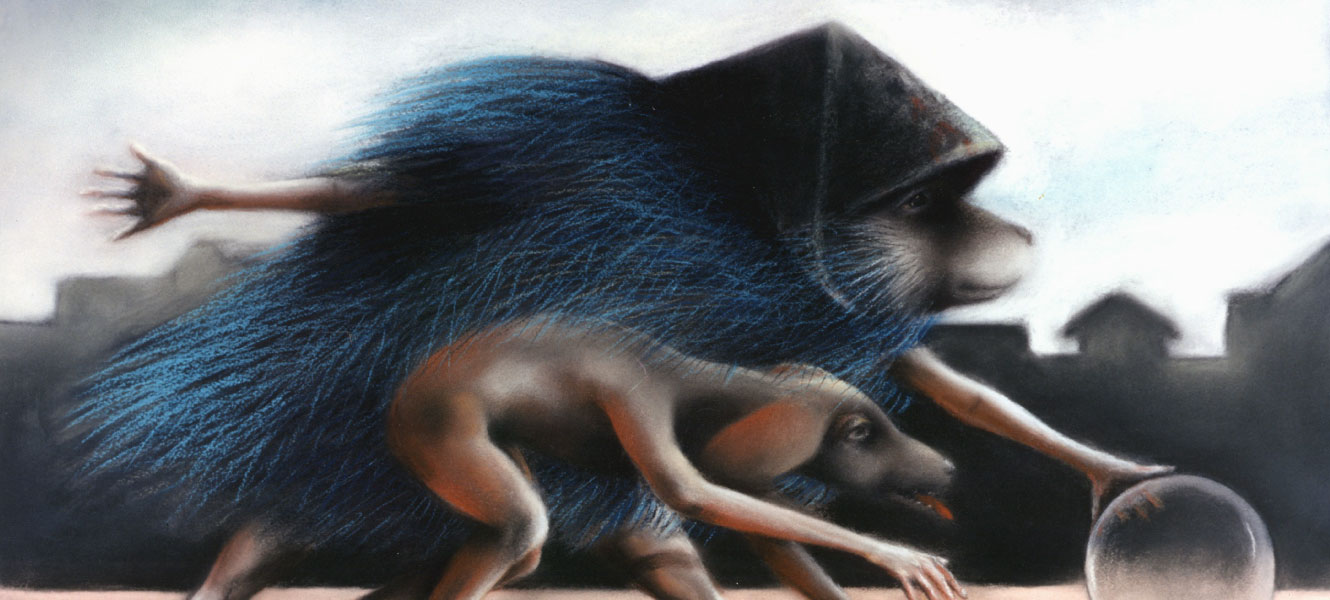

Three Art Objects Evoking the Holocaust

Recently Exhibited in Florence, Italy

I

The three “art” “objects” below, installation, collage & painted triptych, devoted to the theme of the Holocaust deserve commentary: what I see & feel makes me so deeply uncomfortable that trying to get an intellectual grasp on the emotions stirred up has become a necessity. There’s something smug & self-satisfied about these artists’ productions: the smooth, light, falsely captious naïveté of the objects themselves emphasize an inappropriate airiness & lightheartedness, the feeling that they “dashed” them off in a moment of delightful élan. Yet, the Holocaust & comfort must certainly be antonymic. The Israeli painter, A. Arikha, makes a distinction between voir et regarder, between to see & to look at. I will now attempt a brief reading of these artefacts. A hard, bitter, brittle, view, funny, but not really, as you will see. I will not apologize for the droll nastiness, except that an underlying guilt pervades: is there room for teasing or joking? I can’t allow my feelings of disgust obviate my sense of humor. Laughter is only second to music in expressing the transcendent life principle, & represents, in effect, a kind of metaphysical life buoy. However, if I remember correctly, a Hassidic Rabbi said, Men think & God laughs.

This is a junkyard. A Jewish concentration camp junkyard, tidied up so that the Weimar bourgeoisie can say, Well, at least they’re clean. The floor is spotless, well waxed, gleaming. The light bounces off the polished floor: what a cheerful, delightful image of domestic pride. Look, they’ve even put their clothes out to dry (I suppose it must be summertime) & they’ve accommodated our Nazi leaders: they’ve put their books (probably volumes of that dirty book, the Talmud) in a nice centralized pile so that we can burn them. (I thought they had more respect for books than that.) How sweet. How thoughtful. We didn’t think they could be so forthcoming; after all, they are Jews (stingy bastards). Look, they take off their shoes before entering: do you think they could actually be Muslims? Well that’s what they’re called after they’ve stayed here awhile. Oh, really, How interesting. How symbolic. By the way, what happened to the people, where have they gone? No bodies. No Jews. Just things. Things to enhance the stage set for a pouty rapper’s video clip to be shot with the dazzling features of the backyard of a tenement ambiguously tinged with Holocaust objects, torn pajamas, abandoned shoes, barbed wire. This is the typical slum scene of the trendy video podcast. Is this why the artist has removed the stripes from the pajamas?

The second one says: Welcome to our concentration camp kindergarten. As you can see we do not neglect the plastic arts & the children have learned perspective because they’ll need it here (even if it won’t add up to much as they see their parents being murdered). The gay colors & the themes, a doggy, butterflies, a table set for tea, illustrate how pedagogical materials are supplied (each child has his own color pencil set) &, above all, how children, unlike their parents & grown ups in general, are never sad, even if they see their mothers being raped & their fathers naked with their heads shaved & smell the smoke from the chimneys. They just dream & draw away & wait for the barbecue & the wine to be placed on the table. The sole sad note is the tree, which looks like a broken Menorah, & the sinister Arbeit Macht Frei makes a timid appearance, but the schoolteacher painter has carefully hidden these drawings because you don’t want to frighten the Parents-Teachers’ Association (PTA) at the exhibition. Is the crematorium convincing? Is it really a child’s image of what he or she saw in the concentration camps: the stereotyped representation of a smokestack & a brick building, as the painter would like us to believe, as the manifest vision which springs from innocence? This artist has obviously gleaned his ideas from drawings executed by children who attended schoolroom activities organized by the inmates of places such as Theriesenstadt. Who knows, they may actually be reproductions of drawings by children who were trapped in the camps. But what short shrift of the profound meditations & descriptions of Aharon Appelfeld, Imre Kertész & people like Chaim (Gérard) Lewkowicz who was for many years a “witness” connected with the educational program of the Jewish Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris. Chaim, Aharon & Imre were children or adolescents in the concentration camps & they were far from naïve. They were caught up in the hallucinatory struggle concentrated in pure, unadulterated survival that could & did in most cases obliterate the spirit, the imagination & the soul of the individual & cancelled the expectable parameters of moral choice.

The third one says: the homosexuals are persecuted but they remain well fed & are still ready for sex, any kind. They’ll even dress up like Spiderman if that’s how you get your kicks. Don’t let Auschwitz get to you, there’s heartfelt heartbeat techno music & gay bars & costumes. In fact, we’ve got it wrong: this is actually publicity for an Ibiza discothèque. The artist said, What the Hell I’ll just let it hang here any way; it’s a good advertisement, maybe we’ll get some customers after all. Come dance at our cabana “Auschwitz on the Beach”! (No snow, no guards, no holds barred. Laughter & excitement guaranteed. SS, sadistic schticks, offered at cut rates, murder, if desired, at low cost. BRING YOUR FRIENDS. Unaccompanied boys: no entry fee.) Please take note of the delicately tooled screen in art nouveau style evoking an Aubrey Beardsley bordello scene & the quaint Arbeit Macht Frei in shiny, tenderly fragile lettering, slightly askew in the hope that we sense the underlying hesitancy about the veracity of this slogan. A statement of open, perverse, hypocrisy would be a rather vulgar way of saying these things & would probably spoil our fun & make potential customers shirk. The triptych disposition connotes the holy rétables of medieval & Renaissance religious artwork: the homosexual martyrs here are portrayed as victims first & foremost of their sensuality.

II

The three artists represented here really don’t believe in anything anymore. They seem to have forgotten that being Jewish & Jewish culture have something to do with God, religion, mythology & History with a capital “H”. Thinking about transcendence as it connects with human suffering: now they probably would think that that is a « rigid » & “obsolete” way of contemplating the Holocaust. Asking yourself if God is dead, or something like that, is preposterous, ridiculously out-of-date! One might even presume in the light of their work that God is, in fact, dead & that the metaphysical/existential puzzles of religion, & its concomitant ethical thought, have become non-issues. Maybe this is what they are saying: let a dead horse lie.

Is homosexuality only sensuality? Can we believe that? The answer is obviously no. One of the strange, no, weird, perversities of Nazism was its persistent & distorted predilection for medically oriented versions of sensuality, such as its breeding hotels, that were in fact brothels, which have been described so tellingly by the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal in his book I Too Served the King of England. I can’t really bring myself to evoke the negative sensuality, la sensualité négative, of the concentration camp doctors, such as Mengele, & the torturers, such as Barbie, whose sexuality had been reduced to a proto-human stage of development that is if sexuality is understood to be the expression of the life process & the integration of the process & the state of love between individuals & within the human community. As Thomas Bernhard stated over & over again, Nazism was a savage attack on human frailty, the handicapped, children, the elderly & outsiders & on the principle of law & justice whose primary task is the protection of the weak & the lost. The ethical boundaries of the Covenant & the Commandments would have to then be abolished, as well as those who represented them & had remained faithful to them, in order to create & preserve the chaos of total destruction which was the ultimate ideal of Nazism encapsulated not only in the extermination of the Jews but also in the fire consuming all of Europe, including Germany itself, & in Frau Goebbels’s exalted & horrendous murder of her own five children.

As Imre Kertész has said: there were words before Auschwitz; the artist’s struggle is now to find the ones that fit with what we now know after Auschwitz. These words are not to be found in tricky formulations & in commercial copywriting. There are no tricks that fit with Auschwitz. As Kertész has repeated: between Auschwitz, Buchenwald & his Nobel Prize it is very difficult, if not impossible, to establish a connection. He has not found one. The gap is unfathomable. He seems to be asking: What work can actually capture the magnitude of despair attained in the European concentration camps? How can such a work be rewarded? His answer: by understanding it, for this gap doesn’t imply that the Holocaust itself is unfathomable: it is, it was, momentous, like the Ice Age, or the evolving & finally predominant status of Homo Sapiens & begs to be queried & understood: it marks the end of an age & the beginning of a new one in which the unthinkable can not only be thought but has been experienced as a concrete, catastrophic, episode in the history of man. The modern context will always have to bear it in mind. It has thrust humanity into a complete reappraisal of its history &, like the creation & the use of the atom bomb, has shed a long shadow on our conception & our shaping of the future.

Our coming to terms with the Holocaust experience requires our full attention: it is our battle with the angel of death or, perhaps more appropriately, with the ultimate demon of death. Its importance requires our becoming again concerned like the theologians, like the philosophers, like the poets, with the meaning of life itself. Time does not reduce the urgency of our interrogations. Am I wrong in feeling that there is a growing dichotomy between the art works shaped in the hands of those artists who experienced the war & the rise of fascism & the present generation of installation & video artists? Can we hope to bridge the gap between these two worlds of representation? Are we facing a crisis in the basic & essential notion of what it means to be true? Does art still seek truth as the poet John Keats once expressed it, that beauty & truth are the two factors of an imperishable equation? Does this tell us something about our contemporary relationship to history & to intellectual & artistic memory? The Holocaust puts to the test the very important Keatsian concept of “negative capability”: how do we allow ourselves the contemplative doubt that we feel art requires when in fact the extermination beckons us to document & record, leaving us little room for the imagination, precisely because the unthinkable events of the deportation often compel us to perform “photo-reportage”, to make up lists of the victims, to enumerate the horrors, to concretize the physical objects of the disaster, to re-present our feelings of being hemmed-in by the historical facts: the monuments devoted to the Holocaust are massive, often in heavy stone & cement, & leave little space for symbolization. The artist faces here a real & tangible difficulty: the Holocaust causes us to explain & not to dream. The faculty to suspend intellectualized rational judgment & give free reign to understanding through the imagination is something that Primo Levi struggled with; its effective realization in the work of Imre Kertész contributed to his early readers’ perplexity when they approached his writings. Poets such as Simpson, Glastein, Milosz or Rozewicz, not to mention Sachs & Celan, illustrate that, in this instance, poetry is perhaps particularly conducive to the virtual space of the wandering imagination, because with words in music the image is dramatized in abstract & ongoing rhythm & sound & confined inextricably to the dream-screen of the mind.

It would seem that for the three plasticiens of this Florentine exhibition, the following expression applies: l’idea che potesse sbagliarsi non lo aveva neppure sfiorato! The Holocaust has starkly revealed our most frighteningly destructive potentialities. This requires tough thinking & a broad back to bear the burden of knowing & confronting what was once unimaginable, the knowledge that the psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion & the theologian Ronald Niebuhr both, each from his own vector, pressed upon us: that evil & goodness pursue parallel careers; they develop together & compete with each other; the energy required for harnessing the destructive impulses must be greater than the energy that is marshaled to destroy. This is a great moral responsibility. Yes, tough thinking & the deepest & most carefully wrought poetry. This leaves little room for complacently toying with the objects of total destruction & extermination.

The three art objects exposed here must be amongst the worst specimens of les bons sentiments to have ever have seen the light of day. Sentimentality & self-righteousness hand in hand can only give birth to a diabolically perverse progeny, the kitsch that the Austrian novelist & philosopher Hermann Broch shunned & feared as he fled to the United States escaping the Nazis.

The Contemporary Context

In France today anti-Semitism is now a daily issue, the subject of “ordinary” conversation. It nags political debate. Only a few days ago a political demonstration bringing together the most radical opposition to the socialist government degenerated into a violent free for all: it was crowned with the shouting of anti-Jewish slogans & Protocols of Zion styled delusional rubbish. Policemen were wounded. Demonstrators were rounded up & herded into police stations. Some will be condemned for rabble rousing & violence against police authority. Few will be prosecuted for encouraging racial strife. The French standup comic, Dieudonné, has been spewing anti-Semitic propaganda in his performances & on the web for years. He is now in open battle with the judiciary system & the government on this very issue. It has nourished his notoriety & it has increased his following. His racist antics are considered by his followers to be the perfect, lively & fun-loving anti-dote to an environment, a dull, humdrum, conformist social bourgeois social setting, whose inertia & acceptance of privilege is a reflection of its “active” complacency with “Jewish values” & its growing incapacity to make the right decisions & demonstrate traditional (Western, Catholic) moral fiber as well as a reflection of its subservience to an international Jewish conspiracy. You might say, Oh, yes, again. We’ve encountered this publicist before. We’ve heard this garbage before. Haven’t we?

But what is striking is that this new (yet very old & tried) anti-Semitism, in spite of persistent protest to the contrary, continues to be trivialized in many quarters. The victims of history have even become for certain cultural institutions a fonds de commerce, wholesale goods for the cultural “industry”. After all, they seem to say, there’s no business like Shoah business! The images evoked can sometimes be terrifyingly off key, in what in an earlier period would have been called, in very bad taste. The subject is in fact too bitter for this rather out of date expression. But if we mean by bad taste something which cannot be digested, une chose indigérable, something which betrays the nourishment that thought & art must necessarily represent for the individual as he grows from one stage of life into the next, then bad taste, poisonous bad taste, is what we are trying to come to terms with & understand. As Immanuel Kant expressed in his philosophical work, taste & moral standards share, in terms of process, common ethical ground: weeding out the ugly from the beautiful, deciding where beauty & truth concur, reflect the individual’s capacity & freedom to make choices between what is good & bad as well as right & wrong.

When Adorno expressed his deeply felt doubts about poetry after Auschwitz, Nelly Sachs & Paul Celan answered his doubts by writing their poems. As readers we have come to understand that their poems wove the thread, the lifeline, albeit fragile & ready to snap, connecting them to human existence & community. Without poetry their despair & their madness would have destroyed them instantaneously. As long as they wrote they could live & love. At least, this was their hope. The poems of these supreme poets are both anguished & life reaffirming. They say, pain & beauty are not antonymic & truth & pain are a constant conjunction. This is what we face as we struggle to give artistic expression & shape to the unspeakable catastrophe of industrialized genocide as it was carried out in the death factories.

Several weeks ago we were invited to a concert that was to be held on the same street where Dieudonné has his theater, Le Théâtre de la Main d’Or in Le passage de la Main d’Or, near the Bastille. The street was barricaded by the police to prevent Dieudonné sympathizers from assembling in front of his theater, which had been shut down by court injunction. Our names were on a list that a police captain crosschecked to let us pass & reach the concert hall. It so happens that the performer, who is a close friend, is a well-known musical figure in the Jewish community & comes from a family & belongs to a circle of friends who were victimized by the Nazis. Their families & friends in large numbers did not return from the concentration camps. One of her uncles, who attended the concert, had been hidden at the age of five in a hole underground in the backyard of a Polish family’s home during the war. The police became slowly aware of whom they were sifting: the names on the list, the ages of the participants, something about the way things were going, the undertone. The police were actually sensitive enough to voice openly their discomfort & to express their appreciation of the obvious irony of these concertgoers’ identities being checked & filtered once again & this because a notorious anti-Semite’s theater had been closed down. The policeman who was ordered to accompany us to the door of the concert hall apologized to me & said there were times when he hated his job. It will take me some time to understand fully all of the ramifications of this confusing incident. Here again the moral issues concerning personal involvement & engagement as related to feelings & personal principles were being raised in an atmosphere of violence not yet checked by a clear institutional or social framework. Where are we headed, where are we going?

The concert was full of life & energy & vision. This was important, vital, it was, is, the substance of the future & a tribute to the past. It answered again, as art will, the ethical questions as to what is right & what is wrong, without offering, unfortunately, as yet, a palpable, physical, historical solution; it pointed us towards a sense of truth & a possible virtue, the truth & the virtue embodied in the mastery of emotions transformed into a language that could be shared actively & peacefully by the assembly of listeners. The answer to our fears is to be found in education & culture, no doubt. But how is this implemented at large & how can it instigate change, the modification of the moral framework, the moral frame of reference, of society? Why is the infectious beauty & life of art seemingly less contagious than the mortifying virus of racism & brutality?

Chaim

The composer Alek Volkoviski who wrote the lullaby ‘Shtiler, shtiler’ in the Vilno ghetto at the age of eleven illustrates the intense sensitivity & maturity of the ghetto & concentration camp children. The children of the concentration camps must certainly be viewed as being amongst the children of the modern world who have paid & who would epitomize the highest price that history can exact from a child. In these Jewish children’s lives, the wolves & the ogres of the fairy tale emerged into reality & did gobble up their grandmothers & the grandchildren. The obliteration of the protection barrier between destructive fantasy & its concrete, bludgeoning realization possesses apocalyptic dimensions from which recovery can only be at best partial.

When Chaim Lewcowicz initiated my daughter Gabrielle to Jewish traditional music in the first work session we couldn’t get beyond the first lines of the prayer Eli, Eli: when Chaim translated the word flames he burst into tears & had to leave the room to lie down. I thought: Here is a man in his eighties who has obviously cried over & over again & his tears have still not quenched the flames that consumed his mother’s body in Auschwitz. Chaim, who was a living encyclopedia of Jewish music, both sacred & profane & whose Yiddish & Hebrew were impeccable, did return to help us prepare our concert of Jewish music, but here again, the therapeutic limits of art, the music which he so deeply loved & felt as a healing force, remained tangible; no amount of song & singing could bring the final cathartic solace which he so desperately longed for. Chaim struggled endlessly against discouragement. He attended the concert. He was pleased & proud of his student. He said, Gabrielle has learned something about her father & something about herself. Her father has learned something about his mother, Ruth. Car il s’agit bel et bien d’un héritage. But what you inherit must be sifted & thought through, filtered carefully so that the deadliness that may lie within it can become just palatable enough so as not to drown the sense that it is the life energy which has been handed down above all & not only the trauma, the feelings of exile & the haunting images of the extermination. There is the story of my mother’s trip to Germany in the late thirties, her telling us how her father & she dined every evening on the SS Hamburg with the Nazi officials & officers who sat at the captain’s table, the giant photo of Hitler hanging on the wall, & how she served as bait to attract German relatives to the United States, her father’s rather wild attempt to convince them that if they did not board then & there they would never see her again. Her father never let her off the ship. The Nazi terror was thus, in his mind, kept on shore, one landing ladder removed from his child’s vulnerability. But the image of talking to relatives in her stateroom at nine years of age left the indelible imprint of ever-impending loss & despair. Then the unthinkable did occur & the past seemed irretrievably lost for years, taking shape in horrifying thunderbolt shreds of damaged memory. The music & the poetry seem to be one way, if there is a way, to bend the flow of tears towards esthetic experience, giving rise to inner feelings of warmth & hopefulness. The beauty of the Jewish melodies works like a mental salve, scarring the injured mental tissues that were, are, inevitably part of modern Jewish heritage.

Chaim died within a month of the French terrorist Mohammed Merah’s execution of three children & a parent in a Jewish school in Toulouse. Chaim must have seen footage on the TV. He read the newspapers & listened to the news on the radio. It is hard to believe his death was an accident. I wondered, & still wonder, how I, we, can stand the sudden, coincident, crystallization of murderous violence & relentless inner despair? You could say: Eh bien, que voulez-vous, nous sommes faits comme ça. That’s just they way we are. Voilà tout! We it take upon ourselves. On prend sur nous. Eh bien, ce n’est pas vraiment extraordinaire! Nothing to get excited about! There must be some truth to this. We plug on & continue to try to find the words & the music & the images that will allow us to think & continue to grow.

Chaim Lewcowicz felt that we owe our children & our grandchildren, the children of our friends, in fact, the children of the world, unerring stick-to-itiveness. He said: No matter how exhausted you get, never, never, relinquish hope. When his mother was being dragged down into death & suffering from dysentery, the thirteen year old Chaim managed to hustle coffee & drinkable water & reduced potato skins to charcoal to combat his mother’s dehydration. He saved her life in the Lodz ghetto. (His father had already perished.) He could not save his mother from death in Auschwitz, but the tenderness that had fueled his saving her the first time concentrated his deepest memories of affection & love for his mother. The moment of emotional & physical respite that followed her recovery held deep symbolic & psychological significance for him for the rest of his life, however ephemeral it turned out to be. When he was infiltrated into Israel where he began a new life he discovered one day that his brothers were still alive. They had survived the war as soldiers in the Red Army. They were living in Paris. He contacted them. They did not believe he was their brother. So he cut a record of religious music & songs, which he sent them. They immediately recognized his voice & the repertory: only their little brother Chaim, who had been a prodigy cantor in the Lodz synagogue, could sing that way, the sincerity, the skill & the beauty of his singing were inimitable. They were united in Paris & the little brother became the head of the household, built his own weaving machines & became rich. He became a well-loved benevolent despot, giving & lending whenever needed. We listened to his record cut in Israel sixty years before when he was nineteen & only a man who believes in the endless resources of life could have sung that way after the war & the Shoah. It is singing that unites the dead & the living in a heartfelt thrust into life as it is, rich & disturbing.

I very much want to believe that this is how Chaim felt when he passed away, even if his fear of extermination being perpetrated again had been confirmed by the genocides that occurred in Africa, Cambodia & Yugoslavia, even if he feared that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict would be the excuse for the implementation of the effective final solution of the Jews. This fear was a persistent gnawing anxiety that pursued Chaim without respite. The Merah murders were obviously frighteningly close to home. He couldn’t rid himself of the obsessive fear of annihilation in spite of his great self-control in the face of his quarrelsome & not completely unfounded paranoiac anxieties.

Chaim’s home was a grand place on the Eastern outskirts of Paris. Hidden behind trees & bushes, beyond a car port of stone & cement, Chaim had built his home for his children & his wife along an anonymous road that lead the driver & the pedestrian through a suburban landscape of workers’ homes each built according to their individual budgets & their deepest desires for security & luxury. The urban design of the eastern Parisian suburbs does not follow a plan: the mayor’s offices did not, until very recently, overseer the building, the destruction or the renewal of their citizens’ living space: each owner proceeded according to his need & his capacity. Houses protrude onto the sidewalk, gardens are covered with tin & glass roofs to increase floor space & disappear, gateways are corral log fences, castle gangways, high-security prison doors, Andalucían sculpted wood panels with peepholes, what the French call judas, offering a glimpse of Mediterranean patios with potted palm trees struggling to keep alive in the cold dampness of the Parisian basin. Chaim’s house was a discreet mansion behind metal grill electric gates. Safety. Privacy. He had never completed the building of his house, the furnishing of the interior went unfinished & there was a vast reception room whose electrical sockets in the walls & ceiling remained gaping holes. This banquet room was to be a place for weddings, bar-mitzvahs, birthday parties & even shows, musicals & plays & dancing. It had become, because of emotional inertia mixed with his family responsibilities & his trying educational activities for the Memorial, a huge storeroom for Chaim’s weaving machinery, looms & sewing machines & rolls & rolls of cloth & this more so once he had definitively closed down his business & gone into retirement. Chaim had plans for this room: he outlined how it would someday be what it was intended to be, a room for celebrating the beauty & the joy of life. But he was a lonely man: his wife had passed away, his children had to get on with their lives as children do, without their parents. One had moved to Israel. One thing seems sure: it is difficult for children to visit & to live with parents who entertain an unfaltering closeness to the ghosts of their past. This attachment to lost ones who have been traumatically wrenched away in childhood is the common lot shared by all youthful victims of the trauma of war, exile or extermination. This attachment weighs heavily upon the children of the following generations who cannot easily or do not even wish to enter into this communion with the figures of a damaged & damaging past even if they do know that they must share some of this burden with their frightened & hurt parents in order to understand them & even to get on with their own lives. They all know if only subconsciously that recognizing this is tantamount to preventive action against depression & acting in & acting out as opposed to thinking & remembering. Much has already been said on this subject. It is the tug of death, the hug of death, when affection & despair become too completely & darkly fused.

I have a friend, Catherine, whose grand parents died in the Lodz ghetto. When she learned that I knew Chaim she asked if she could meet him. I talked about this with Chaim & he assured me that he was willing to answer her questions about her grandparents, but he was to choose the meeting-place. He chose a wildly noisy hotel lobby on the Place de la République. We sat at a large table where intimacy was automatically proscribed & we tried to compete with the loud music surging from the ceiling loudspeakers. Fashionable beautiful people couples shouted to each other from table to table, laughing & raising their glasses to toast. Serious conversation was impossible. Chaim was happy. This is where he liked to come & meet people for the first time. Things happen here. It’s chic. Catherine tried to pose her questions. Chaim listened distractedly & finally said: “I didn’t know your grandparents. You know, there were a lot of people in the ghetto. Why don’t you do your research the way everybody else does it, at the Memorial? Go to Poland & have a look at the place yourself. Of course, you’re not going to find anything.” You’re not going to find anything. I realized how sad Chaim really was. The din would not drown & smother his suffering. He bore the emptiness & the darkness everywhere:

I fool about with my night,

we capture

all

that tore loose here,

your darkness too

load on to

my halved, voyaging

eyes,

it too is to hear it

from every direction,

the incontrovertible echo

of every eclipse.

(Paul Celan, trans. Michael Hamburger)

During those same years, when I was interpreting the role of a clarinet playing rabbi in Grigory Gorine’s dramaturgy, the Kaddish, based on Scholem Aleichem’s tales of Tevie, the Milkman, & we were seeing Chaim regularly, a piano student of my wife’s asked us to read a book that his grandfather had written. We were astonished to learn that this boy’s grandfather was the famous Henri that appears at the end of Chapter 9, The Drowned & the Saved, in Primo Levi’s If This is a Man. In Levi’s book Henri is a cold & calculating fellow ready to muster all of the resources of his education, intuition & cultural refinement to survive within the concentration camp & of course, even beyond the concentration camp. To Levi, Henri was a young man “….intent on his hunt and his struggle; hard and distant, enclosed in armour, the enemy of all, inhumanly cunning and incomprehensible like the Serpent in Genesis.” Levi concludes his description of the young man with: “I know that Henri is living today. I would give much to know his life as a free man, but I don’t want to see him again.” Our student’s grandfather read Levi after Levi had committed suicide. Levi’s posthumous beckoning urged him on to write. In reading his grandfather’s answer to Levi, the grandson would learn who his grandfather was & had been & what his early adulthood in the concentration camp signified. Until then, hardly a word about the deportation & the concentration camps had slipped through his grandfather’s lips. The grandson had read Levi’s damaging description of his grandfather. This was not the man he knew. But his grandfather’s silences took on a new meaning.

What Primo Levi did not know was that Henri’s capture & removal to the concentration camp withheld a riddle, a kind of internal, fatal, secret contract connecting Henri forever with his loved ones. When the French police appeared at Henri’s parents’ home to take him away, they apparently deliberately left him alone in the kitchen with the back door open. It seemed an obvious invitation to escape. Henri did not avail himself of this opportunity. He waited for them politely, passively. If my memory is correct, this was repeated during his transport to Drancy. He did not flee & with hindsight he thought he could have, perhaps even should have; he was convinced that the police had acted consciously on his behalf. The misfired offer to escape remained a mystery & a source of puzzlement for him for the rest of his life. But in fact, it seems, he could not bear to not join the members of his family who had already been shipped away. He was both discouraged & fatalistic. His brother would die in Auschwitz. He was not the completely cold, calculating, cunning person that Levi thought he was: what initially brought him to Auschwitz was an overwhelming sense of fidelity & helplessness; greed or the necessities of strict survival were not his guiding principles. That apparently came later once he had lost everything that was meaningful to him. He wrote his book. Did it bring him relief? He died shortly after its publication.

Chaim was alone in his house. He had laid down to rest. Rest. While he was lying there was he thinking of all the young people he had lectured to & with whom he had become friends? Did he think that others would carry on his work, that his témoignage would continue to be remembered by young people, nourishing their ethical investigations & queries? Did he realize that he would be missed if he shut his eyes to the world & to life? Rest. What Chaim needed was rest. He was tired like the little cigarette vendor, Isrolik, in the ghetto song: tough & resilient, sad & deprived, singing gaily in spite of it all, but also deeply aware that he was, sometimes, just whistling in the dark. If Chaim thought & believed we knew that we would & could not rest, then perhaps, he had found something that could be called peace. Of course, I’m sure his foremost thoughts went to his family. A Jewish woman doctor friend, commented to a patient: I have spent years participating in seminars encouraging young Jews to get on with their lives & to protect themselves from a morbid harkening to the past: understanding & remembering the past does not necessarily imply being trapped in it emotionally. The young people have got to overcome the despair & keep away from the hate. But each time a grandchild of mine comes into the world I find myself muttering to myself, Well, at least they didn’t & won’t get this one. This thought takes me completely by surprise at each birth. I say to myself, it’s easy to preach.

I think Chaim was found at daybreak. He was found lying in his bed. The house must have been steeped in silence. In that remote house only his “governess”, as he called her, & her middle-aged son, lived below in the downstairs apartment. I imagine nothing stirred. I was told that when they found him he seemed to be in a deep sleep & serene. Did his face, as it sometimes does in peaceful death, reveal the young man he once was below the old one? In any event his rested body would not reveal the torment that I can’t help thinking must have preceded his passing away. He longed for peace & quiet, but the world as he saw it would not give him that. That we all knew. In my mind’s eye, he re-reads the accounts of the Toulouse murders & decides he can go no further. He must lie down & rest. Alors, de l’étoile de l’aube, le jeune Ange aux yeux tristes et aux ailes immaculées, tendait le Calice des larmes muettes-et en recueillaitlarme après larme dans le silence de l’aube. ‘Then, from the morning star, the young Angel with the sad eyes & the immaculate wings extended the Chalice of silent tears & collected tear upon tear in the noiseless dawn.’ (Chaim-Nachman Bialik, Le Livre du feu, The Scroll of Fire.) Silent tears when words & action have come to a full stop. When we are finally, completely, alone. When music becomes absorbed into pure, enigmatic, abstract thought, the music of the spheres.

We Cannot Rest Yet

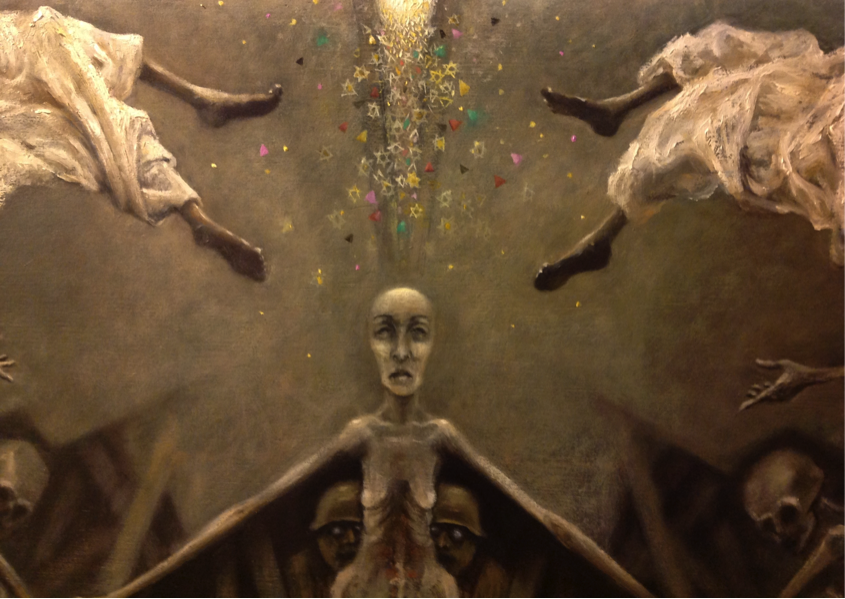

“Shoah” by Rebecca Hayward-Bellugi

“Shoah” by Rebecca Hayward-Bellugi

We cannot rest yet. Charred & famishedbodiesgleam with the grey-white sheen of ashes. They are herded together under the rigidly brandished salute of deux démons exterminateurs cambrés dans leur tension de perpétrer le mal (two extermination demons bent to the snapping point as they perpetrate evil) who, with their free hand brush the exposed thighs of two helpless women who shelter their head & face with upraised forearm & try to turn & twist away from the wickedness. The light descending upon this agonizing mass is the poisonous gas of extermination disguised as a decorative, vaporous, beam, a shower of colorful badges once woven into the striped uniforms of the persecuted. These last will find rest only: when the white hovering, floating, skeletal souls above can effectively smother the death angels with the striped prayer shawls sewn with the cloth of the concentration camp uniform or, in another perception of the painting, when the white hovering, floating, skeletal souls can effectively take grip of the persecutors’ cape wings & rise up out of Hell & reach the open sky; when the powder of Nazi symbols raining down upon the bodiless woman’s bald head (or are these symbols, in fact, projectiles exploding from her mind?) becomes the soft sprinkle of morning sun, a blue dawn veiled with a soft & tender golden haze of reborn truthfulness, free of fear, of terror & of dying in the hands of the gruesome Nazi winged spirits; & when, at last, the skull of the white Minotaur steer, driven by the almost invisible helmeted bloodshot mosquito insect creature in the background, overwhelming & powerful like a tidal wave, is pulverized & reduced to nothingness. This painting, this pain thing, roars with the din of starvation & the burning of flesh & soul. Its cold & stark symmetry reveals the purposeful & unforgiving organization of systematic & total destruction. It is a forbidding image & it endures woefully. It is still alive. “Alive” is here, indeed, a strange word. “Alive”. Yes, in perverse guise. To be “alive” in this picture is to live a life struck by the absolutely negative valence of cancelled being, a primitive energy to end all life, a mental & physical form of anti-matter. If death is stasis, then this is not death yet, it is its process: this is certainly more horrifying than the abstract experience of nothingness which is perhaps another way, a technical & bodily way, of defining “rest”. Stillness: to lie still, to be at rest, to feel, at last, nothing, as opposed to the terrifying anoxia which lingers on the threshold of death. To hover, to be short of death, to experience violent death prolonged as entertainment: the Nazis, in their search to annihilate man, his body & soul, the heart of being itself,created & perpetuated this inconceivably cruel limbo. This purgatory of prolonged, slow, torture was the Nazis’ supreme metaphysical achievement: pure suffering souls without bodies, without flesh or muscle.

Orphan

Un enfant demande : « L’ouïe est-elle fine ? »

& le silence du soir le sépare du monde.

Ces visages à l’ombre de la maison natale m’appartiennent.

Serrés, debout sur la pelouse, les adultes avancent pas à pas,

au confluent de leurs rêves.

Un ange passe, disent-ils. Un ange.

Ils s’immobilisent.

Ils n’entendent plus le résidu du conflit

qui perdure. Au pied de la palissade, dans l’herbe,

l’enfant repère les gemmes dispersées du drap mortuaire.

En ramassant les tessons, ses mains

sauvegardent les prémisses du deuil.

Ses larmes vives inondent sa chair de lumière noire.

Il se réfugie dans les plis chiffonnés d’une galaxie ancienne

accueillant dans son sanctuaire sa gravité insoutenable.

Il s’éteint dans l’instant qui suit.

Hannah Arendt has described our foremost task as adults in her recurring emphasis on the absolute centrality of remembering & thinking: thought, remembrance, are the cornerstones for developing a deep sense of responsibility, this is what the parent must do for & with the child; this shared reverie is what the child learns to reproduce within himself when he is alone. The philosophical “divided self” is in fact the dramatization of a constant dialogue with the inner voices of those who have loved & raised us. This dialogue expands with the experience of sharing thoughts with others for the entire span of one’s lifetime: these dialogues become part & parcel of the conversation that arises in solitude within the divided self. The richness of this internal dialogue could serve perhaps as a definition, or as a yardstick, for intellectual growth & could constitute the fundamental framework for the educational experience. Of course, the trauma of the extermination or exile or war has required many children to re-create the internal thinking parent & those parents who survived these traumatic events have sometimes beckoned their children, in an involuntary reversal of roles, to become the thinking parent, to become the mother or the father to the suffering parent unable to formulate the words or focus the thoughts that the surge of uncontrolled & “misguided” feeling & pain seems to elicit. I knew a man who had been a member of an extermination kommando in a concentration camp who was suddenly faced with having to put his own father in the gas chamber. When he said to his father, I will stay with you, we will perish together, his father ordered him to live, to strive diligently for his survival, for now, he said, your purpose in life will be the birth of the children of the next generation & you have been thus designated as a witness, my, our witness: your life will be devoted to thinking, remembering & trying to understand. The wound of this unthinkable moral dilemma never healed completely. This man became a doctor & had a rich & fulfilling life. Nevertheless, the guilt & the pressing inner doubt obsessed him & seeped down into the next generation. Suicide, the quiet drift into a silent & distant, metaphysical galaxy, remained a constant temptation. There were moments when oblivion & thoughtless activity pushed thinking & esthetic experience into the background. There hung the premonition that the mind, if left to roam the inner reaches of despair, would dissolve to never be recovered again. Some things, some things probably essential to mental survival, were left unspoken, unsaid, not thought through. He would lose one child through suicide. It is impossible to establish a cause & effect relationship here, because secrecy & mystery represent, in this respect, an infinite, unknowable dimension. But it is troubling to note that this has been repeated elsewhere & I have observed it in my immediate environment of friends & acquaintances. The list has unfortunately developed into a litany of farewells. I have struggled with this list all my life. It still remains to be put into words or music. Some day I hope it will take shape as organized artistic expression: as it stands, it remains the unfinished task of a lifetime.

Lotte

Lotte Scwharz would visit regularly during the mid & late sixties. Lotte was a writer & well-known avant-garde pedagogue. My father had become close to a political scientist living in Canada, Hans Blumenfeld, who was an old friend of Lotte’s. He introduced my parents to Lotte. Born early in the twentieth century, her activities led her to be present at all of the major philosophical, social & political upheavals of the century, in Moscow, Vienna, Berlin, etc. She was a Marxist, a member of the French Jewish Resistance & saved many Jewish children’s lives. When she thought she was going to be separated from her young daughter during the war, she cut a record: on one side she dictated a personal statement to her daughter, an oral farewell letter, & on the other she recited, read, one of Rosa Luxemburg’s Letters from Prison. I did not hear this record. But my mother mentioned it often.

My parents had found a small town house in an hameau, a “mews”, in the fourteenth arrondissement in Paris, near the famous rue Daguerre. My mother & Lotte were sitting in the living room: my mother with a tall glass of wine & Lotte with a small glass of brandy. It was early spring & the lilac trees in the front garden were in bloom. The evening breeze carried the perfume from the blossoms through the windows. The stillness & the sweet & fragrant air & the dull golden brightness of early evening light as the sun sets in Paris, suddenly became for me arrested time, time captured, as if the rich peacefulness of a very distant past had suddenly materialized, a time before the Holocaust.

But in fact, Lotte had brought with her a long-playing record of Ghetto songs arranged by the French composer Lasry. My mother & Lotte asked me to place the record on the record player & to be sure to turn up the volume. This record still stands, from my point of view, even in this period of Klezmer infatuation, as one of the most beautiful renditions of this particular musical repertory. The woman singer began to sing, accompanied by Lasry’s lush orchestration. The two women wept in silence. When the record came to an end they said nothing & dried their tears. Their conversation resumed, chitchat about family & friends & serious talk about education. We had dinner: my mother was an extraordinary cook & there was always lots of wine. They were both in a very good mood. When Lotte left, my mother said: Now, that’s what I call a perfect evening.

Many years later I visited Lotte with my wife in Bonnieux, in the south of France. We had concerts at the Chartreuse de Villeneuve-les-Avignon & at the Abbaye de Sénanque. On our day off we went to see Lotte. Time had stopped, again: on that hot afternoon the fragrance was a mixture of herbes de Provence & lavender & the sunset was red & sharp with radiance. Lotte wanted me to drink her cognac. She did not introduce us to her friends who were sunbathing in the garden. They did not speak. Their eyes were closed. They were very still. My wife mentioned later seeing tattooed digits on their arms. I said, I think these are the adults who had once been the children that Lotte had taken into her custody after the war. I felt we had intruded. I was glad to be off & away, because I did not feel that we belonged in this very private world of hers & her children of the war & the concentration camps. But I was glad to have seen her all the same. I knew that this could be the last time I would see her.

Time stopped on the evening when Lotte visited my parents & when we were seated at her table in her garden overlooking the valley that stretches out below Bonnieux. I have puzzled over these moments when time stops. I have experienced this when listening to classical Indian music, particularly to the wooden transverse flute of Panalal Ghosh as it floats above the enchanted drone. Time stops & feelings well up, nostalgia, or some hitherto unconscious, unexpressed desire that the harmony of the moment will endure, endure forever. Time stops here as it stops in dreams. Dreams tell stories, with beginnings, middles & ends, but do they belong to time? They unravel in an unearthly space where time is not, because time in its layers are see-through, you can see all of the layers at once & you can even see the future, the future as an emotion, as an emotional state of being, as a thing in palpable time. Yet we know this future is an invisible, improbable future, because it is peopled with the sensations of our past, our acquaintances & our loved ones, transformed, bent to fit the obscure meaning the dream provides & is inviting us to interpret when we awake, when we awake to & into the present. When we awake, it, the future, slips between our fingers & vanishes. The past looms in the forms of images, words & sounds replete with powerful emotion. We hear the tick-tock of the alarm clock on the shelf next to the bed & the beat of time marches on. In the stillness of the garden, time hovered before the downbeat, issuing us into the rhythm of an unending season: Lotte would be alive forever. My mother’s love for Lotte would be alive forever. My mother had been orphaned & I felt, in an oblique way, that Lotte represented a maternal figure for her, an engaging & demanding mother who had welcomed & would raise with a much desired moral firmness the lost children of the Holocaust, the children of exile & trauma. My mother & Lotte shared a moment of eternity together, even if they were themselves surrounded by death, enshrouded in the Ghetto songs or in the still & haunting presence of Jewish war orphans.

I had not spoken to Lotte for years after our visit to Bonnieux, when one day she phoned out of the blue. She wanted advice about buying a saxophone for her grand daughter who had once been a student of mine, in fact the first student of my teaching “career”. I said I would be glad to take care of it myself. We got into an argument. Our words were harsh. Suddenly our voices flared up. The argument was about who had been her grand daughter’s first teacher: she had forgotten that I had been her grand daughter’s first teacher & she insisted that it had been a colleague of mine, a person I had actually recommended when I returned from New York during my University studies. I was deeply hurt. I felt she had forgotten how close we had been. I was once a part of the family. It was ridiculous of course. I knew how infantile my reaction was, but that’s what happened. I agreed, nevertheless, to send Lotte a catalogue & told her when I could go to the store & try out instruments. She called again and said, They’re too expensive. Are there cheaper versions? I answered, Well, in that case your grand daughter can go to the store & fetch the instrument without me. Below the price range I’ve sent you, all of the instruments are the same & do not have to be tried out. But I wouldn’t buy an instrument that cheap, because, in fact, they’re very heavy & very hard to play; they’re all out of tune. A few days later I received an angry letter from her, accusing me of having become an unfeeling capitalist American cynical monster. Her handwriting was very shaky. I could tell she was having memory problems. She was old & tired. I had misunderstood the entire situation. I did not go to see her though. She died. I had not seen her or written her. I should have. It was a far cry from the serene twilight moments we had shared when I was younger. Regret is a weak word here. I had not felt for her. I had wronged her. I think now that I could not bear her getting old. I could not bear her dying. I suddenly hated the burden of her feelings. She was demanding. She had been kind & careful to so many children after the war, she had remained faithful to her ideals. She had become a creative writer in the latter years of her life as revealed in her book Les Morts de Johannes. But Lotte was vulnerable. Lotte’s vulnerability was troublesome, a nuisance. Lotte’s supplication had become irrecevable, unacceptable. Lotte was life without disguising the rough edges which are so much a part of it, life which is anchored in the disturbing & wonderful experience of living with & understanding (& misunderstanding) others, trying to cope with oneself & with the pressures of time, of the times. I had to accept that her strength, her generosity, were not, in the end, unwavering. I had wished them to be so: after all, she was endowed with the power to arrest time, to suspend the pressures of history, of memory, of the uncertain future. Youth often fails here: it asks much of former generations who have been to war or suffered economic or political deprivation.

My failure to grasp the situation was, is, as I see it now, beyond my blatant & crass immaturity, an unfortunate illustration of the “épaisseur” de la vie, l’âpreté et la rugosité auxquelles nous ne pouvons échapper bien que notre plus profond désir nous incite à rester alerte à la dimension du temps inestimable et précieux qui passe, nous appellant à rester, ainsi, disponible pour l’autre sans jamais quitter le registre de la pensée et de la sensibilité, nous encourageant à rester fidèle à une éthique qui serait, idéalement, irréprochable d’attention et de délicatesse dans notre rapport à autrui. Life is thick skinned: we can’t escape its toughness & its sharp edges when dealing with others in spite of our deep wish to attend to time passing, its inestimable worth & preciousness, as it urges us to never relinquish our thoughtfulness & our sensitivity, to remain faithful to an ethical stance ideally crystallized in an unimpeachable concentration & emotional delicacy towards the Other. The unconscious is unforgiving, it tells you what is what as it sees it, often when you least expect it. It has no qualms about time or place. It has its own conceits. The experience can be painful; it can be exhilarating; it is always food for thought, conscious thought. The demands of the unconscious often challenge our rational ethical choices. Lotte was old & tired & I had turned my back on her. I didn’t want to face her pain, her pain of leaving the world she so much cherished in spite of her trials, her pain about a world that to her mind was still the same, her nagging & bitter realization that violence & injustice still reigned. I did not see the saxophone as a metaphor: she could still give this musical thing to her grand daughter. This gift’s significance went far beyond the actual instrument, whatever its price. I had cheapened it. It was like her voice on the record to her daughter: what counted was the music of the words; who cared about the vehicle anyway; it was all about music, feelings in music, feelings that escape words. Furthermore, Lotte had given into jazz, the shamanistic music of the spiritual healing of the African American, she who was so full of gemutlichkeit of the central European intellectual classes of another era. I should have understood this. I should have accompanied her.

There are times when I would like to erase the Holocaust, times when I don’t want to think about it anymore, ever again, times when I would like to forget. But I can’t, because it is about people. I can’t forget Lotte. I can’t forget Chaim. They can be heroic & generous, but they can also forget who you are or what they have meant to you. People are not coherent when it comes to your needs. Who you are to them is sometimes an insignificant detail, especially when they have been to Hell & back. Their attachments shift often as they bless you with their love of life & their attention: their parents & sons & daughters & wives & husbands & friends perished in the concentration camps. They seek them in others. Their quest is endless & perhaps hopeless. They need our affection more than we need theirs. Of course, many have passed away now. In some ways the whole kit & caboodle of emotional & philosophical anguish could thus vanish letting more pressing, contemporary, issues take their place, justifying forgetfulness, a definitive turning of the page. But our acquired knowledge stemming from the emotional & moral experience of our friendships with the generation that survived the Shoah endures & will endure as our affection for them endures. If we think that affection is the necessary pre-requisite for the shared reverie in thought & remembrance that shapes esthetic & artistic expression, which, in turn, sets, I believe, the premise for faith in a hopeful future, in a possible future, then we can agree with the American poet, David Schubert, who asserted that affection is our only antidote to melancholy & I would add, to loss, as well.

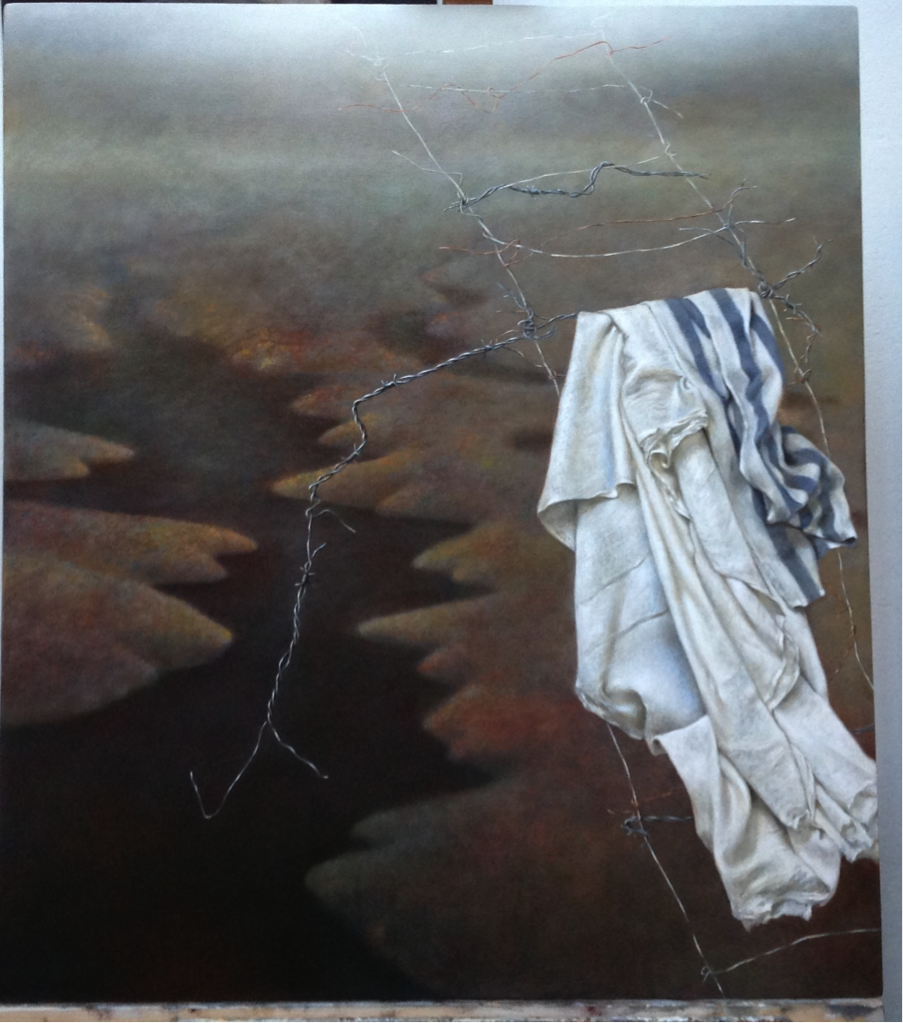

Jacob’s Ladder

Rebecca Hayward-Bellugi, my sister, continued to work on Jacob’s Ladder. The background landscape had materialized into a river & desert shores, dunes, hills & creeks; the barbed wire’s lines were further defined, sharper, more metallic & more cuttingly ominous. She asked me, Is this painting finished? Do you think I have finished this painting? What have I done to my painting?

With the unfinished landscape, in the first version I saw, the hovering barbed wire rungs & the wind-blown prayer shawl were perhaps more “celestial”, objects rising in suspension & reaching for the heavens, in spite of the ladder’s strange admixture of brutality & fragility. The hosts of angels could still appear in this irresolute & ethereal atmosphere: like twisted rosebush tendrils deprived of blossoms the ladder issued from nowhere & reached up into the sky above clouds in golden twilight. Or was it the Earth we saw & not clouds? Then this Earth was far removed & was itself cloudy & intangible, a vague dream-like memory, to which the climber with the shawl had consciously bid farewell. The shawl was a shredded, forlorn soul, but remained spiritually alive, an abandoned angelic garment.

With the Earth brought to full realization in the final version our vision underwent a radical shift in emphasis. Our sensations were steered in an opposite direction. We feel & even know now that this ladder is rooted in earth, perhaps embedded in the pillar shrine marking Jacob’s encounter with the Divinity, his dream vision of the angels ascending & descending the ladder: but no God stands at its peak, amongst the clouds, promising Jacob & his family prosperity & happiness. The shrine of piled stones has perhaps crumbled: the land is burnt & barren & the river is streaked with red, the red of mud & pain & fire & perhaps even blood. The river’s waters do not flow. Time has become thick & slow. The shawl is snared, caught on the barbed wire, is drawn downwards towards the earth: it has lost its airiness; our eye is caught by the stiff wire protruding from the rung from which the shawl hangs, severing the painting in two, dividing the painting in its center, drawing a dividing line between the light of heaven & the parched earth. It is a weird lightening rod: useless, an injured object of imprisonment & torture. This wire has been ruptured & damaged, worn down, worn to a frazzle, yet it will still penetrate hand & foot. This barbed wire is an archeological remnant of a cruel & broken past: battlefields, concentration camps in ruin. The Earth is an uninhabited steppe. It is in a deep silence. No voice cries out. Everything has died in this painting. The shawl waving aimlessly on the barbed wire rung of Jacob’s Ladder (and I would add, Without its Angels) is what remains of the believer, or perhaps even humanity. The shawl, with no one to wear it, is a lonely realization. This is the barbed wire ladder of the Shoah: the absent God & the absent believer, who has perished perhaps from a fall from the ladder, are now forever conjoined. This nightmare eradicates the potential sacred peacefulness that has inspired so many people to get on with their difficult & troublesome & even tragic lives. No wonder Rebecca did not know if the painting should be finished: it begs us to imagine a world so desolate that life has come to an end. Where do you go from here? The painting obliterates the very notion of divine grace or intervention & with it the dream of a rich future as redemption.

Hans Jonas, the philosopher, continued throughout his lifetime, to explore theologically oriented philosophical concepts in his search to offer strong argument for keeping faith & not relinquishing hope. Many Jews have asked themselves why God was silent during the Shoah. Many non-Jews have re-examined their religious beliefs in the light of the Shoah. Where was the all-powerful & omniscient God during Auschwitz? How could He have been indifferent to & absent from the suffering & the evil that had seized the world? In answer to this, Hans Jonas has proposed a radical re-evaluation of the definition of God: the Holocaust has made God’s vulnerability central to our representation of Him. Jonas argues that God’s withdrawal safeguards the ontological principle of being that “all is within all”. The holocaust has revealed Him to be, in contrast to Job’s representation, a suffering god who has renounced his omnipotence. Jonas feels the Deus absconditus is contrary to Jewish religious tradition: God is never entirely hidden, nor entirely unintelligible. God has withdrawn from the concrete unfolding of things by renouncing those potential satisfactions that His omnipotence would permit Him to glean from his perfection. God suffers with man because, by definition, he can neither hinder nor alter the becoming of the world: God guarantees the continuous unraveling & development of being. Hans Jonas conceives God in the pursuit of His limitless task of being, as a worrying & caring god that suffers with his creatures as they struggle with life, time & history. Hans Jonas does not think God is absent, unreachable or dead. He believes, perhaps as Etty Hillesum believed before him, as revealed in her war notebooks, that man must come to God’s help, that only man can bring to fruition, within himself, the kingdom of Heaven & defend it. Man alone is “responsible”, not God, the fountainhead of existence. The Quorum of the Righteous, the Just, in the opinion of Hans Jonas, is thus vindicated as central to our understanding of moral responsibility in the light of divine transcendence.

I realize that all of this is rather abstract, conceptual. As I write it though I feel very sad. Hans Jonas’s philosophical inquiry betrays urgent feelings of moral & psychological despair. I discovered them unwillingly: they lie hidden within & beyond Jonas’s abstract formulations. I was talking about Jonas’s theory with one of my very intellectual students & I was surprised: tears welled up & I had to choke them down by pretending to cough. I thought: No concept can answer to or absorb my, our, sorrow about the Holocaust. The Holocaust in its process of mass dehumanization crystallized man’s ingrown fear of loneliness, of a complete severance from the comfort of human understanding & sharing. It is noteworthy that this extreme experience of loneliness frequently results in a complete loss of any sense or feeling of self-worth, of personal dignity: the “muslims” of the concentration camps, the sunken-eyed inmates who perished out of sheer depression, are an illustration of this, the loss of any sense of self-value entailing a loss of any interest in life. The metaphysical query, which posits the presence or absence of a god as essential to human existence, represents an abreaction to the fear that humanity can be potentially drained of its substance, the substance of communication, thinking & living together. Theological thinking has expressed through its emphasis on transcendence how much the human imagination seeks the comforting perspective of a systematic, all enveloping, & hopefully benevolent, presence that will guarantee man’s place in the flow of time & history from generation to generation. This is precisely what God promised Jacob from the top of the ladder as His angels “ascended & descended on it”.

The ladder in the painting is certainly the ladder of martyrs & not of angels. It elicits metaphysical query by the very nature of its subject matter: God is absent: by His absence He offers no words of comfort or solace: by his absence He offers no prosperity, no future. He even refuses to be angry, to offer an explanation of the Holocaust as Destiny, as punishment for the breaking of the Covenant. There has been no true prophet of the Holocaust: God’s silence has been total. The believer has abandoned his shawl on the ladder & no angel will appear to redeem it.

The painting’s stark representation of despair beckons us to action, or it at least can be construed as a call to action. It faces us with the moral problem of either merely accepting per se the brutal fact of total extermination, the ladder of pain leading nowhere, or, our fighting back & refusing the fatality of history. I think this is part of the question, Is this painting finished? If it is finished & we see it as a landmark of unending despair, we are left with the bleak notion that it transpired, this is it, eccoci qua. This is as far as we go: a dead end. But it is, by the very nature of its bleakness, in a literal sense, an unfinished project: we cannot allow ourselves to let the image have the last word. It is in fact, “just” a painting. This is vital: it is an artifact springing from the imagination & an uncanny demonstration of fine painterly craftsmanship. It is thus a push forward. It is uplifting. It begs us to break the spell of the despairing image—& see the painting as process, as thought unfolding, as if in sacred ritual.

Painting seizes & captures a permanent state. It is time arrested. Here is an eternal moment, a bad dream, that won’t go away. But this is why, in spite of the fixed image, the painting must be experienced as process. The process of the painting must be part of our understanding. The end result, as we stand before the painting, could be suicidal despair. But the making of it, the dynamic creation of the image, says that it, the scary, hair-raising message, belongs to a life process of the mind in search of understanding. It is a dream captured, albeit a frightening dream. The craft of painting a dream is a serious game, a deadly serious game, the playing out of a fantasized form of philosophical thought. Like all games, it is a form of release, a release from the pressure of time, from the pressure of emotion: it actualizes our freedom as we explore the relationship between our secret, intimate world & the world as it is in its mystery.

Jacob’s Ladder is a painting. This tells us something more, something else, something at once concrete & metaphorical, and something both deeply human & deeply spiritual. It tells us that the ladder, the enigmatic metaphysical ladder of imagined transcendence, can be painted, that Rebecca Hayward-Bellugi, a painter living in Florence, in the year 2014, has seen it, has touched it, has climbed it & left, of her own will, the shawl hanging on the upper rungs as a banner, the banner of a woman who waves to us from above, who has been there & has returned to share her carefully hewn image of despair & says it can be represented, remembered, thought through & experienced. There is great beauty in the light. The light radiates from above. There’s still hope. There is great beauty in the cloth. Cloth: the child swaddled, the beggar clothed. It is there to be plucked from the rungs of barbed wire. If Rebecca has placed it there then some one will be brave enough one day to climb this ladder in his mind’s eye & place the shawl on his shoulders & drape his head with the shawl again. Because the ladder was painted, repair & consolation can be at last accomplished through thought & the imagination, our only means to go back in time & start anew. This is why the painting will never be finished: because we must climb the ladder over & over again to retrieve the shawl with which we will adorn our children at the bar-mitvah ritual.

Many years ago I attended a bar-mitvah ceremony at the synagogue on the Rue des Tournelles in the Marais, Paris. When my friend covered his & his son’s head with his shawl, it was like a bird taking his chick under its wing, a protective gesture preceding the chick’s decisive lonely leap into the air, the adolescent’s leap into manhood & responsibility. Their heads huddled together in prayer, they whispered in unison those words that the boy would bear in his heart as he joined the community of men. The boy’s commentary before the congregation was erudite & sophisticated & obviously memorized. Did he really understand it? I don’t know. The scholarly cantor who assisted the rabbi in getting this boy to write his text was visibly pleased: the boy had worked hard at turning his words into music. This is what we can, or must, do: add words, poems, stories & dramaturgy, to Jacob’s Ladder & possibly, if we are inspired to do so, music.[1]

A Toy

In the Jewish Heritage Museum devoted to the Holocaust in New York City you will come upon a game of snakes & ladders designed during the Thirties for German children: to win the game the Jewish pawns must be gradually eliminated: the moves are determined by throwing dice. The child who has freed Germany of a maximum number of “contaminating”, “ugly” & “grouchy” Jews is the winner.[2]Apparently this anti-Semitic game board was a best seller during the prewar period. The transformation of the Jewish deportation, represented here as a salutary premonition, into a traditional European children’s game is certainly a crystallization of the perverse Nazi hatred of Jews & life in general, the hatred that so much preoccupied the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard who believed that the Nazis, in spite of their imperial ideology & the notion of the One Thousand Year Reich, wished, at bottom, to obliterate the future, the very notion of a future, & perhaps the very notion of time & history, by destroying not only the Jews & other minorities, but all youth. This hatred of the young is what Bernhard describes in his book Origin, A Mere Indication. The snakes & ladders game of the museum with its playful use of prejudice, contempt & hatred, is not only demeaning & destructive to the Jews & their culture & their history, but it is also as Alfred Jarry has coined it, une machine de décervelage, a “brain excavator engine”, to the children who would engage in it, perhaps poisoning & crippling their minds forever. This programmed distortion of a child’s game into a conventional jeu de société is all the more horrifying to someone who works, as I do, on a daily basis with young children, because only the very disturbed proto-fascistic child conceives images & activities of such a violent, murderous, dimension. Such children do exist, in very small numbers. Nevertheless, it is striking to observe that racial hatred is almost completely absent from children’s games. Rivalry, jealousy, envy & ordinary hateful, mean behavior, exist, of course: but they rarely take the form of total destruction which greatly terrifies the child, who is also subject to feelings of intense guilt & remorse; children never envision or plan ethnic cleansing, unless encouraged to do so by adult ideologues who stand above & outside the child community & steer them in that direction. Who were the adults who created, sold & bought the Let’s Eliminate the Jews snakes & ladders game? What was their vision of childhood? How did they reconcile the hatred in the game with its playful purpose? What had happened to the child-of-their-own-past: had it perished within themselves? What did singing & laughing & joking mean to them? Were these people really having fun? [3]Did they really think this game would entertain & amuse their children?

Much has been said about the children, both Jewish & non-Jewish, of the interwar period. But I feel there is a dimension that deserves perhaps our special attention: did they see each other? Did they share the experience, the drama of disappearing from each other’s lives? Did the non-Jewish children broach the subject with their elders? My impression is that the non-victimized children ignored, or pretended to ignore, what was happening around them. Children have great powers for denial & repression: in some circumstances it is the sure road, the “royal road”, la voie royale, the only road, to mental, & sometimes even physical, survival. This is certainly one aspect of the situation: children had to let the adult world take care of its self, as they hunkered down into their own world of serious games of the imagination & deep understanding without necessarily being able to avail themselves of the clarity & the aid of verbal formulation, the latter taking shape later in adulthood after much introspection & self-exploration. The German author W.G. Sebald who came to measure the horror of the Holocaust when he was a twenty-two year old young man & sent to study abroad in Manchester is a case in point. His pilgrimage to the poet & translator Michael Hamburger’s home in the South of England traces his inner journey towards historical & emotional truth as he comes to realize that in England he has met part of the Diaspora of survivors of a destroyed culture & population, a culture hounded & persecuted by those he had hitherto called “my people”. During his childhood & during his adolescence he had lived in a bubble: the sociology of post war Germany cannot explain away this “innocence” for which he would later express great perplexity. The naïveté persisted also because as a child a world so perverse, a world so destructive, had to be kept to one side, outside of mind & sight, otherwise growing up becomes an almost impossible task. At least, this is how I see it & this is what I believe: there is just so much a child can take. Il faut que l’enfant louvoye avec certaines réalités. The child sometimes has to dodge the facts. But, as opposed to adults, I would not say the child is lying to himself: he has no choice. The weights & the measures of the moral dimension of a child’s choices between or judgments about good & evil, good & bad, cannot be aligned with those we apply to adults.

Nevertheless, Jewish children & their parents were asked to face unthinkable moral problems & dilemmas about death & survival: those who have survived, like A. Appelfeld or I. Kertész, who were teenagers at the time of the Holocaust, have now become, literally, cultural heroes, but they themselves evoke “accident” as a determining factor in their survival. Most children perished, their choices & options obliterated: everything had become hazardous & aleatory, except the perspective of almost certain death. There were variations in the paths leading to it, short cuts & side paths, chemins de traverse, but the end of the road was always, in the minds of their keepers, death.

The absence of choice is at the core of what the American philosopher Thomas Nagel, in his book Mortal Questions, has called “moral luck”. As Nagel has put it: in spite of moral questions being contingent on history, circumstance & external conditions, we nevertheless judge people by what they do, because human beings cannot give up their autonomy completely to external agency, which would be tantamount to relinquishing their capacity to think & make decisions. This is exactly what happened to Jewish children: they had to give their lives up completely to an external, murderous, agency requiring unthinkable life & death choices.

Very few people have experienced choosing between horrible & more horrible or truly evil & most evil. The mother or the receiving doctor on the landing ramp chooses between her two children. The brother in the line lets his sister walk before him & go first & switches to the able workers column. The adolescent closes the door behind his father & bolts the door to the gas chamber because he is told to do so under threat. In this case, the absence of being able to make any reasonable moral decision for the better is, without equivocation, a psychological disaster for the individual who is thus deprived of experiencing or expressing an essential human characteristic in his development towards maturity & responsibility & perhaps even happiness: the urge to do good & what is right, what Immanuel Kant deemed a “sparkling jewel”, the will to perform good acts. To be absolutely barred from the good or the expression of good will must be the very definition of a form of hellish punishment: it surpasses in horror Dante’s Circles of the Inferno, because within the Holocaust framework, morality & spiritual torment & guilt are no longer issues to the punished as in Dante’s poem. The total absence of being able to opt for what is intrinsically good & life-giving concentrates unfathomable dehumanized physical survival, une survie corporelle déhumanisée & insondable, aggravated by brutality imposed from without & beyond control. Survival no longer reflected sifting out right from wrong: this is survival without the expression of love & its protective ties of solidarity. It runs contrary to human instinct. As the Polish writer, Tadeusz Borowski, a victim of the concentration camps, has so well illustrated in his book, This Way for the Gas, Ladies & Gentlemen, there was little room for protective & resistant heroism: heroism incurred almost instant death. Punishment was meted out sans réserve: punishment delivered to victims whose sole “guilt” was a terrifying ideological construct elaborated in the minds of their persecutors. Hell & punishment without reason, just for being a Jew.